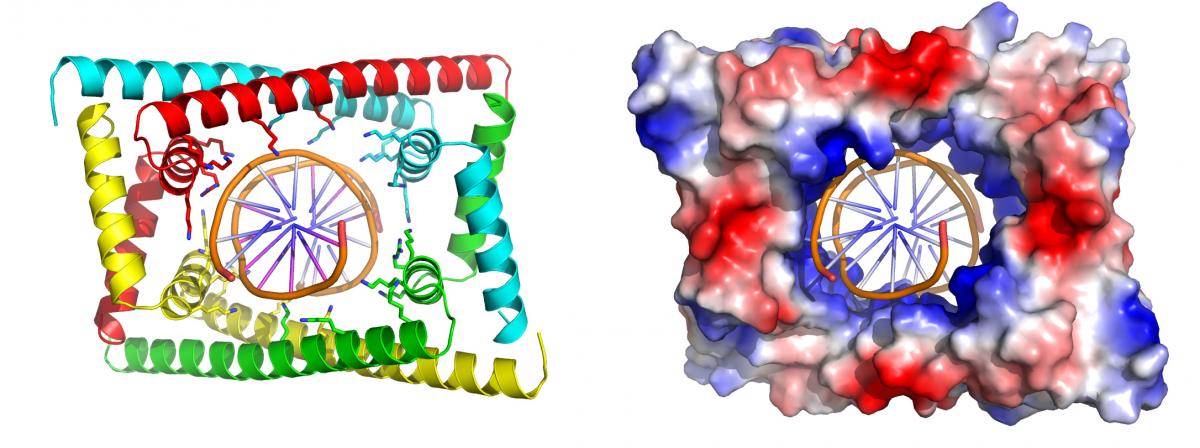

Work by the Laub and Schumacher labs at MIT and Duke reveals a novel DNA binding clamp essential for replication in C. crescentus. The DNA in cells is on the order of 1,000-fold longer than the cell in which it resides. Hence, it must somehow be condensed while also permitting critical processes such as replication to occur. Compacted DNA, however, leads to supercoiling, which makes impedes this process. Replication begins at specific regions of the chromosome where specialized proteins separate the two strands. However, this local separation tangles the rest of the molecule further and without intervention creates a buildup of tension, supercoiling, preventing replication. Enzymes known as topoisomerases, which travel ahead of the strands as they pulled apart, untwist and rejoin them to relieve the tension that arises from supercoiling. Topoisomerases were generally thought to be sufficient to allow replication to proceed. However, the Laub lab at MIT and the Schumacher lab at Duke revealed that an additional protein, called GapR, in the bacteria, Caulobacter crescentus, is essential to drive this process. In bacteria that lack GapR, the DNA became overtwisted, replication slowed, and the bacteria eventually die. The crystal structure of the protein bound to DNA, solved by Duke’s Schumacher, revealed that GapR recognizes the backbone of DNA, rather than the bases, forming a snug clamp that encircles the overtwisted DNA. However, when the DNA is relaxed in its standard form, it no longer fits inside the clamp suggesting that GapR sits on DNA only at positions where topoisomerase is needed. Future studies will be needed to determine specifically how GapR promotes topoisomerase activity.